American Teenage Financial Literacy is Just…Average

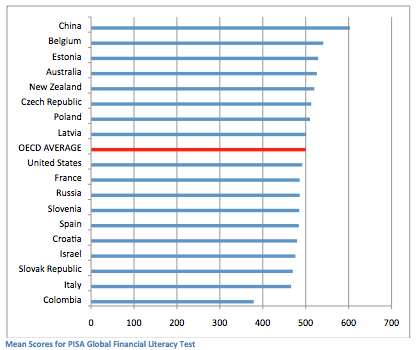

Teens in the United States are only average when it comes to financial literacy; crushed by Chinese teenagers’ remarkable performance on the Programme for International Student Assessment’s (PISA) first-ever financial literacy assessment.

PISA typically surveys an average of 65 countries and economies focusing on mathematics with additional reading, science and problem-solving areas of assessment. On July 9, 2014 PISA released the results of a new financial literacy assessment evaluating 15-year-olds from 18 countries and economies. Among those countries the United States ranked somewhere between 8 and 12; China, 1. But that’s not all, while the U.S. struggles to handle their finances, students from Australia, Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, New Zealand, and Poland perform above average, meaning above the U.S.

The results show that more than one in six U.S. students does not reach even the baseline level of proficiency in financial literacy. PISA defines financial literacy as “the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, and the skills, motivation and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society and to enable participation in economic life.”

The struggle for financial literacy is not confined to one nation. World-wide, countries and economies that participated in the assessment had an average of 10% of students that could analyze complex financial products and solve non-routine financial problems, while barely 15% could make simple decisions about everyday spending.

The PISA study also examines schools’ resources and finds that the equitable distribution of resources is a major challenge for countries around the world. Even when schools have high quantities of resources, some of them suffer in terms of their quality.

Even more surprising are the findings that deal with school curricula. The report says:

Some countries have begun to introduce financial education in their school curricula; others focus squarely on strengthening students’ conceptual understanding in key areas, such as mathematics, and then expect that their students will be able to apply that understanding in different contexts, including financial ones. The fact that the latter group includes top performer Shanghai [China], whose students show higher proficiency in financial literacy than those in any other country, even though they are rarely exposed to problems set in financial contexts in school, shows that the question of how to develop financial literacy is still very much open to debate.

At the U.S. release of the PISA financial literacy data at The George Washington University, Annamaria Lusardi, Director of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC), led a discussion with key experts on the organization’s findings as well as the barriers and opportunities for improvement when teaching these concepts. Many experts addressed how American education is “an inch deep and a mile wide” suggesting that students are exposed to a wide variety of subjects but they are never given the opportunity to specialize or deepen their understanding any further than a semester or two of study.

Chinese education is an example of how conceptual understanding in limited key areas can provide transferable skills and knowledge that can be applied to a broad range of tasks. As Andreas Schleicher, Director for Education and Skills at OECD, said, the economy rewards you not just for what you know, but for what you can do with what you know. Exposure is not all that students need.

Some people argue that financial literacy courses need to be given to students at a younger age—even starting in Kindergarten—and that these courses need to be more rigorous. Butting heads with this idea is the concern that teachers are not prepared to teach this subject because they were not taught themselves, or because they have not faced the same complexities of the financial world that youth face today. Financial education may have to start with parents and teachers.

PISA provides an extensive view into what other countries are doing to teach financial literacy along with the results of their teaching and it provides an opportunity to examine and reevaluate our own education system.